I often get the question (typically after a grueling drill that leaves students gasping) “How do I improve my conditioning?” More often than not, the answer is “Train more Krav.” But sometimes your personal schedule doesn’t align with the class schedule, or maybe you train every day and still feel your fitness isn’t where you’d like it to be. For the former, some of the ideas in this post can “fill the gaps” in training. The latter case can use this post to strengthen weaknesses for an overall training improvement.

For the great majority of practitioners, Krav Maga alone will more than meet their needs and desires for fitness. Krav Maga will certainly get you faster, stronger, and develop a bigger gas tank, but having a solid base level of strength and conditioning makes all of those attributes in the context of Krav easier to develop. Once you’re strong and fast in general, you can focus on coupling those attributes with the specific skills of Krav Maga instead of just trying to catch your breath between front kicks.

Can you get in great shape training only Krav Maga? Absolutely. You can get stronger or faster, though not necessarily strong or fast. This is not in any way a deficiency of Krav Maga, which is why I use the word augmenting rather than supplementing. It’s a self-defense and fighting system after all, not a strength and conditioning program. The system is designed to develop fitness through self-defense training (and vice versa), but even a staunch supporter like me won’t fool you into thinking doing Krav will improve your raw deadlift strength or help you win a 5K race. There is some minimal cross-development for sure, but just as you must spar to get good at sparring, you must lift or run to get good at those things.

This is the difference between general physical preparedness (GPP) and specific physical preparedness (SPP). Applied to Krav Maga, this translates to the difference, for example, between doing burpees to improve your basal conditioning for sparring and training focus mitts or actually sparring to improve your sparring conditioning. In other words, doing burpees will improve your endurance, but can’t directly equate to the real thing—sparring. (Take one more step back and see the macro view: Training Krav Maga is itself both general and specific preparedness for the real event—defending yourself against an attack on the street!)

So, if nothing equates to the real thing, why bother augmenting training? Two reasons: One, whether due to equipment, training partners, or safety, you can’t always train your “event”, be it sparring, grappling… or a street fight. From the previous example, maybe I don’t have a place to spar outside of class, I can’t find someone to spar with, or I want the cardio benefit but just don’t feel like getting hit on a given day. Second, if you train harder than your event, you’ll have a physical and psychological leg-up. I’m willing to bet that if you get better at a grueling, CrossFit-style metabolic conditioning (metcon) workout, a few rounds of sparring will feel like a warm-up by comparison.

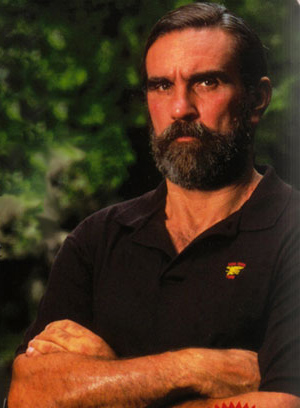

Both of these reasons also the support The Krav Maga Macro View: We make our self-defense drills as realistic as possible to mimic the physical and mental stress of a real attack, but they’re still drills with safety guidelines. We try to make them as taxing as possible so that you’re physically and mentally prepared for a time domain far longer than that of an actual self-defense situation. As SEAL Team Six founder Richard Marcinko said in his Ten Commandments of SpecWar, “I shall punish thy bodies because the more thou sweatest in training, the less thou bleedest in combat.”

But why is it important to be “fast”, “strong”, “powerful”? I can answer that with one of my favorite Mark Rippetoe quotes: “Strong people are harder to kill than weak people, and more useful in general.” Fighting skill sets and all else being equal, who has better self-defense odds: the “average” woman or the woman with a high strength-to-weight ratio who can run, lift, jump, etc.?

This sounds great in the abstract (at least I think so), but selecting a program—and you need a program—is no easy task. There’s a lot of bogus information out there that can be at best a waste of time and at worst counterproductive, even harmful. In case I’ve implied otherwise to this point, let me clarify that I am neither an expert in the realm of strength and conditioning nor a fitness all-star. I’ve merely done a lot of independent research and experimentation. I will only comment on training programs I have personally used. These aren’t the only training programs or necessarily the best programs for everyone. I suggest these as a starting point, but always do your own research as well.

- Ross Enamait programs

I really can’t say enough good things about Ross Enamait‘s training methods. Not only are they fundamentally sound and effective, but they’re specifically geared towards combat athletes. He has two programs, both of which I have used to great personal success. Ross’ basic approach is “low-tech, high-effect” using minimal, often homemade, equipment. Oh, and buckets of burpees…- Infinite Intensity: This program combines both weight training and bodyweight training. The program itself is set up over 50 days, but Ross also offers some ideas on how to modify it to your schedule and needs. There are strength training days; GPP workouts that are typically body-weight based metcons; and Warrior Challenges that typically add weights to a longer conditioning workout. Sprinkled in are sprint intervals and core workouts—and these ain’t no silly crunches.

- Never Gymless: This program is similar in set-up to Infinite Intensity, but removes the need for most equipment (a medicine ball, pull-up bar, and resistance bands are recommended) by basing the workouts on variations of fundamental bodyweight exercises.

- CrossFit

The goal of CrossFit is “increased work capacity across broad time and modal domains”, or developing the “capacity to move large loads over long distances, and to do so quickly”. The main site (www.crossfit.com) posts a Workout of the Day (WOD) in a three days on, one day off format. The workouts and content on the website are public (i.e. free). The workouts are “constantly varied functional movements executed at high intensity”. They range from performing as many rounds as possible (AMRAP) of a circuit in a given time, performing a given number of rounds as fast as possible, powerlifting or Olympic lifting movements for max weight or reps, a run, etc., etc. So much has been written about CrossFit that I don’t need to repeat it here. Following these workouts will build a second-to-none level of GPP, and you’ll never get bored. One of my favorite CrossFit-isms from creator Greg Glassman: “The needs of the elderly and professional athletes vary by degree, not kind.”

CrossFit is “infinitely scalable” to ability and equipment, which is vital to success and safety, and also when you don’t have access to some of the more obscure equipment required now and then. Many affiliate websites have “on-ramp” programs that are designed to gradually develop proficiency in the fundamentals, and most of these websites have their own WODs that tend to be a little more grounded in equipment reality.

The negatives of CrossFit: there’s a pretty steep buy-in of equipment, basic skills, and a manual’s worth of nomenclature, acronyms, and catch phrases. There are ways around the equipment issue, but no way around investing some time upfront learning the lingo and training the basic movements in a context outside of timed workouts. If you’re really into this kind of stuff, it won’t be a chore. But it’s daunting nonetheless. Also, its lack of perceptible programming may keep you a little too scattered in your skill development. Finally, working out at full-bore intensity can lead to burn out or injury if you don’t do some self-imposed periodization.

More reading: - CrossFit Football

CrossFit Football is an offshoot of CrossFit developed by John Welbourn for power athletes. The Workout of the Day is split into two parts. The first is the Strength WOD (SWOD), which is usually a powerlift (squat, bench press, press, deadlift, or variation) or an Olympic lift (clean and jerk, snatch, or variation). After a 10-15 minute break is the Daily WOD (DWOD), which is in the style of the CrossFit.com workouts but typically a little shorter and more often based on power (explosive movements like sprints, box jumps, power cleans, kettlebells, etc.)

For what we do as Krav Maga practitioners, it’s my opinion that CrossFit Football is better suited than CrossFit.com. I love “main site” CrossFit and agree it’s one of the best general physical preparedness methodologies around. But focusing on a solid strength base and shorter, power-based conditioning seems to me more applicable to self-defense than some of the 20-30+ minute puker metcons of the main site.

There is also more of a perceptible programming behind CFFB WODs that I prefer to not knowing whether I’ll be running 5K or pulling a one-rep max deadlift tomorrow. It’s also easier to gauge progress if you’re not “constantly varied” to the point of being random. - Kettlebells

It doesn’t get much more hardcore than kettlebells. They’re beastly iron tools of Russian strength training, for crying out loud. They’re incredibly versatile and are less expensive and more portable in comparison to most other equipment. They promote functional and dynamic strength due to their off-balance design, which also allows for swinging and explosive lifts that are not as easy or effective with dumbbells. Do some circuits with a heavy bell and tell me you’re not ready to wrestle a Siberian bear! Don’t get caught with one of those 5-lb step aerobics infomercial kettlebells, though…

It doesn’t get much more hardcore than kettlebells. They’re beastly iron tools of Russian strength training, for crying out loud. They’re incredibly versatile and are less expensive and more portable in comparison to most other equipment. They promote functional and dynamic strength due to their off-balance design, which also allows for swinging and explosive lifts that are not as easy or effective with dumbbells. Do some circuits with a heavy bell and tell me you’re not ready to wrestle a Siberian bear! Don’t get caught with one of those 5-lb step aerobics infomercial kettlebells, though…

I suggest these resources:- Pavel Tsatsouline’s Enter the Kettlebell

- Art of Strength

- Mike Mahler

What’s great about P90X is that it improves your strength in fundamental bodyweight-based exercises: push-ups, squats, and pull-ups. You’ll do so many reps and variations of these exercises that you can’t not get good at them. What’s not so great about P90X (aside from the heavy infomercial shtick) is that some workouts are devoted to less functional exercises like biceps curls; there are cardio workouts, but no grit-your-teeth conditioning workouts; and, perhaps most important of all, if you’re doing any other physical activity (like, uh, Krav…), the schedule will most likely burn you out in short order. Also, when I did this, I subbed a Bas Rutten MMA Workout for the Kenpo-X day because it was both less lame and more beneficial skill-wise.

Again, none of this will make your self-defense techniques better. Don’t think that strength equals fighting ability. You must train, say, gun defenses to be good at gun defenses. What we’re seeking with an augmented strength and conditioning program is a higher level of general physical preparedness to provide a foundation on which we can more successfully apply the specific physical preparedness and skills of Krav Maga training. All of this, in turn, prepares us for our ultimate goal of actual self-defense.

Part II will be posted later this week and deal with augmenting Krav Maga with other skills training.

Epic post Patrick and I really don’t have much to add other than make a plug for Crossfit. I’ve been doing it for almost 3 years and you are right about the steep learning curve but nothing will get you more functionally strong other than wrestling bears professionally. The is a great Crossfit Affiliate less than a mile from Brian’s

http://crossfitnewton.wordpress.com/getting-started/

You can take the on ramp class on Mondays and still get to Krav at 8:15.

Hi Patrick,

This was a very appropriate article for Krav Maga students and any athlete for that matter.

One thing to consider that you didn’t mention was that most people have rounded shoulders from poor posture, being overweight, having sedentary occupations, driving too much, watching too much tv, training show muscles and not go muscles and from fighting a lot (Krav)

Upper body pushing exercises (push ups, bench press…) and especially overhead lifts (military press, push press, clean & jerks, snatches) can enhance your performance in Krav, but for the large majority can really hurt you in the short and long terms if not balanced out by an equal or greater total amount of work from pulling exercises (db rows, inverted rows, dead lifts, external rotations, Y,T,W,L, seated rows, and pull ups/chin ups if done properly…) .

Most every fighter you see has rounded shoulders and probably some anterior shoulder pain, neck pain and possibly some headaches too. Increasing your work volume on presses without matching it with pulls builds muscle and strength on top of a problem that increases your risk for injury.

Fighters at the minimum should use a 1:1 pull to push ratio with push being 2nd and for most Krav enthusiasts a 2:1 ratio. If you have pain, a 3:1 ratio would be a good starting point for pulls to push.

Fighters with any history of shoulder pain or who currently have rounded shoulders should seriously consider NOT doing any overhead lifts as this greatly increases your risk for injury.

This doesn’t mean you still can’t train hard or use a myriad of exercises, this just means you can train for more years and enjoy greater health and performance longer.

Thank you Patrick for this article and your writing in general. I enjoy it.

Mike

Thanks for the insight, Mike. Important and relevant points.

I can’t quantify the breakdown, but I would say that the Ross programs, CrossFit, CrossFit Football, and especially P90X all have a good balance of push/pull. Pull-ups, rows, band pulls, etc. are frequent workout components. But, yes, the preponderance of movements involve pushing. If only we could find a place at the school for pull-up bars…

Here’s an interesting article on overhead lifting safely:

On the Safety and Efficacy of Overhead Lifting

Pull Up Bars could be suspended from the ceiling, inside of the ceiling tiles and/or suspended from the ceiling and attached to walls above the mirrors allowing enough space for people to swing w/o kicking the mirror. The reverse of most crossfit set ups.

Also could attached eye hooks to wall and use TRX or equivalent for pull exercises.

You could do the following body weight exercises for the posterior chain (suitable for beginners, deconditioned people and people with rounded shoulders) in class:

1:31 Backside Bridge, Alternating Tripod

1:50 Floor Slides and then Wall Slides

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=18tTkfLmNfo

0:16 Dead Lift to High Pull (intermediate)

0:20 Dead Lift to Speed Snatch (advanced)

0:46 Seated Band Row

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=u0GCvwOzjG0

Bent-Over Y, T, W & L-Raise

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5-k67cmNf2w

DB Row

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FymJOXzNPNU

Scapular Push Ups

http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=voPnXh5_aG8

also plank rows are a great body weight exercise and frog squat to a T or Y-Raise are great warm up exercises.

Regarding the OH Lifting article:

That was a great article, by competent and credentialed people. I do overhead lifting myself, it’s awesome both show & go muscles and is safe when done properly.

If you have existing shoulder issues in the form of pain or poor posture, I’d recommend against starting with overhead exercises and instead starting with:

Soft tissue work via a massage, foam roller or lacrosse ball on your t-spine, lats, traps, pecs and hip flexors.

Static stretching for your lats, pecs, levator scapulae and internal rotators at both 0 and 90 degrees.

Mobility exercises for your T-Spine in both rotation and extension, glenohumeral in the form of arm circles forward and backwards, hip mobility in the form of leg swings (linear & lateral), 1/2 kneeling hip mobes, split squats, lateral lunges, drop lunges, figure four glute pulls.

Stability Exercises in the form of planks, side planks, back side bridges, scapular push ups.

Pre-Hab Exercises in the form of Y, T, W, L’s, external rotation at 0 and 90 degrees, wall slides, neck slides, thoracic wall walks, side-lying internal rotation.

Strength Exercises such as:

X-Band Pulls

Horizontal High Pulls

Neutral Grip Rows

Straight Arm Lat Pulldowns

Dead Lift Progressions

1-Leg Bridge Progressions

Stability Curl Progressions

Lateral & Linear X-Band Walks

Looks like I rambled on. I wouldn’t necessarily use all of the above, I would pick the one’s best appropriate to the individual and incorporate them into your overall strength & conditioning program so that you have a more full & balanced program.

Again use the 3:1, 2:1 or 1:1 pull to push ratio depending on your current pain & posture status. The only time I’ve ever done a 1:2 or a 1:3 pull to push was working with D-1 Collegiate Healthy Athletes (football primarily, but also crew, track…).

Very much enjoying the writing Pat. Hope to see you in the fall with the return of a.m. classes.

Mike